articles

Foreword

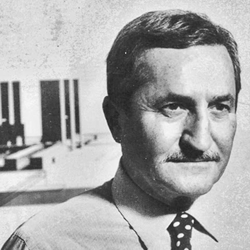

Carlo Aymonino

It is true that architects move around a lot. They build in many places and leave signs of their work here and there. But Panos Koulermos is different, because his work is rooted in every place he has been involved with. He leaves disciples and often buildings behind.

If we look in particular

at his mature projects, we can see that the plans are always

calm and controlled, logical and consequential. Open and enclosed

spaces are well articulated and beautifully proportioned. The

elevations are considerably more complex. They are not simple

projections of the plans, but visual panoramas generated by

an interplay of elements and plans at different levels. Two

recent designs, the Nursery School in Los Angeles and the Greek

Pavilion at the 1991 Venice Biennale, illustrate this well.In

both cases the plan is rich but extremely ordered, while the

elevations, and the formal expressions in general, are strong

and fascinating, forcing us to read all the parts that constitute

the overall design.

Koulermos’ work acknowledges

that not everything can be new every time. In some projects

in Greece and California, certain design resolutions and forms

are used in anticipation of future development or adaptation:

the rotate square, the slab block that completes the composition,

and the diverse structural systems drawn from elegant and appropriate

models.

I am reminded of some other friends of the same generation, Constantino

Dardi and Gustav Peichl. Though very different to each other and to Panos,

they nevertheless operate in the same free manner within the established

modern and contemporary tradition where the old masters form the base

and they are the new generation. Their work is also new and 'orderly' at

first glance, but, looking deeper, it reveals itself as exhilarating and full of

surprises. Koulermos may make reference to the old masters of Modernism

- sometimes he evokes Kahn in the organisation of bays or the use of

irregularity within a regular framework - but his buildings are essentially

the product of his own energy, his own talent for innovation.

Koulermos has learned from the way the ancient Greeks integrated the

built space into the landscape. His work relates to the context of a place,

to its history and geography, in much the same spirit as Palladio’s villas

relate to the Veneto landscape, or Béla Bartók’s piano pieces relate to

Hungarian popular music.

In Crete, Koulermos has recently had the opportunity to build a number

of projects for university facilities, which represent a summation of his

work to date. These interventions are not tied together by formal similarities or a partially repeated architectural language, but are independent

buildings, distinguished by their location and context and, above all, by

their identifiably different conceptual aims. The design of the first

complex, the Research Centre of Crete, is based on an axial organisation of

three highly differentiated buildings, which are combined to form a larger

composition with a compact and articulated plan that generates an equally

differentiated volumetric expression. The project for the Foundation of

Research and Technology, on the other hand, is a much more linear design

- a real 'slice of the city' within the new campus.

This book presents

an extensive documentation of the work of Panos Koulermos over

the past fifteen years. But it could also be considered as a

testimony to his future work, for he is constantly developing

his experience. Everything he does builds on what has gone before.

Bad Monsters Make Way

John Hejduk

Panos Koulermos is in love with architecture

and his work proves it. Panos knows about form, space and, most

importantly, about spirit. Of course he should because he comes

from that part of the world where such things are honoured and

celebrated. Panos has stories to tell and we listen to him.

He makes us happy to know about the various fates of man and

also of woman. Panos understands that the ancient gods are always

waiting, observing our creations; that is , they compare and

finally judge. I think they smile with and upon Panos Koulermos.

In their positions, the gods need their hearts to be warmed

a bit as do we humans, and Panos provides us with the necessary

heat, just enough, for he does not want to burn us. He is clear

about the ambiguity as to what the heavens might bolt down,

so he makes an appropriate offering, that is , the offering

of good work in the form of architecture.

I imagine part of our friendship is due to

our similar respect to the time honoured generators of architecture.

We both love white surfaces where the sun and clouds can

do their work. We respect the shadows and the shades. We think

that the site, the plan, the elevation, the section and the

detail are weights enough in which to express our imaginings.

We are suspicious of the facile, the extravagant, the noisy.

We believe in structure and construction. We are the enemies

of chaos and of de-constructions. We abhor the mindless and

exaggerated visceral. We celebrate the invention of programme

and the explorations into the unseen. We revere our discipline

and we enjoy eating with each other. If ever I have to take

a dangerous voyage, I want to have Panos next to me. He has

the ability to make bad monsters make way. He laughs them to

death. His oblique rationale speeds up their disappearances.

I always look forward to seeing my friend again. With him, one

is still able to talk about the square, the circle and the triangle.

At this moment of his life, Panos is

having a remarkable spurt of energy. He is moving like a bat

out of hell or a man out of hell or a man out of the labyrinth.

His architecture on Crete/in Crete is extraordinary; wonderful

plans, solid geometries/volumes bathed in unrelenting sun/light,

the mastery of large programmes, elaborate requirements made

into imposing structure, cities on a hill, at once hidden and

seen. One can be assured that these are joy-full places of learning

and discovery. How refreshing to see an architect making precise/simple

architectural plans. Panos loves columns, beams, piers, wall,

stairs, ramps, windows, balconies, cylinders, cubes, earth modulations,

bridges, floors, ceilings, lightwells, skylights, doors , entries,

arches, masonry, plaster and steel. He uses the above as an

alchemist would. His chemistry is judiciously mixed.

I want to extract out and speak to/of

two of his most recent projects that provoke thought - thoughts

about time , our time, past time, new time, old time, time within

time...The two projects are the Nursery School in Los Angeles

and House 12 in Ithaca. In a way they encapsulate the conditions

we confront today.

The Los Angeles Nursery School presents

the diabolicalness of the outside conditions if our cities,

the compressions upon the innocent and the proposition that, like

the monasteries of the Middle Ages, the schools of today are

becoming the refuges and protectors of our youth and their freedom

to learn. Panos' school presents certain problems head on. He

understands that our educational institutions are under attack

and he makes a monastic/defensive proposal. One can inter/change

the programme: stated school/unstated refuge. Also, the undertone

as school for sunlight, air, and school as penitentiary, schoolyard

as playpen, and schoolyard as minimum security exercise yard.

The Los Angeles Nursery School plan is quite simple: three cylindrical

volumes in a court surrounded on three sides by a volumetric

wall-walkway-rampart; the fourth side enclosed by a two-story

volume which contains kitchen/dining facilities plus administration,

toilets, etc. Basically a normal nursery school . Taking the

same plan, two other institutional programmes could be imagined:

a monastery and penitentiary. For the monastery, the surrounding

narrow walkway could be considered the cloister walkway, enclosed

and overlooking the cloister yard . The three cylindrical volumes

could perhaps be the monastery chapel, library and meditation

areas, with the large vaulted structure serving as kitchen/dining

and administration along with sleeping facilities. All told,

a reasonable plan for brothers.

The

second programme/plan could be conceived as a penitentiary, with

the encircling outer wall-walkway, the elements for security

guards overlooking the prison exercise yard. The Three cylindrical

volumes could be used for the prison work areas, and the fourth

elements, the vaulted rectangular volume, for administration,

kitchen, dining, sleeping, toilets, and so on.

I speculate about this because I believe

plan/programme can be interchangeable, as shown in the above

case either for learning, for prayer or for incarceration. It

is eerily strange that our times seem to need all three. In one

case a joy-full programme, in the other a thought-full programme,

in the third a chilling programme.

Panos Koulermos' Los Angeles Nursery

School could be thought of too as school for angels that provides

for prayer so that the angels are not captured and imprisoned.

The project House 12 in Ithaca is a beautiful idea and seminal

work. I am deeply moved by it. It is a land ship, a house ship

that a modern-day Ulysses would have to engage, Whatever his

trials and tribulations, at least the ancient Ulysses always

had a water ship, a ship that floated upon the liquidity of

a fluid. Panos' modern-day ship/house is tied to the land. Its

fate physically is to be static and fixed. The oar-like structural

buttresses are at once ancient, medieval and modern: the wood

of antiquity, the concrete/masonry of the Middle Ages and gripping

of modern earth.

I believe Panos is saying that with

all our apparent modern-day mobility we in fact have become

more fixed, more internal, more inaccessible and, in a strange

way, more private.

In response to his

land/fixed ship, I can live within it. That is , I can think

within it, I can pray within it, and I can travel throughout

the world within it. And most important of all, I can imagine

it.

I think somewhere or other Le Corbusier

has stated that the only thing transferable is thought. Panos

Koulermos helps us to understand.

First published in the catalogue to the Panos Koulermos exhibition

Topos, Memory, and Form, shown in 1990 at he House of Cyprus,

Athens.

My Greek Friend

Francesco Dal Co

The first step towards knowing more

about the work of Panos Koulermos is to consider the details

of his biography. Koulermos was born in Cyprus some 50 years

ago. He studied first at the Polytechnic of Central London (PCL),

where his training was in the hands of personalities such as

Douglas Stephen and Thomas Steven. After graduating, he worked

for a number of years in London. However his contacts with Italy

increased and in 1960s he moved to Milan, which was one of the

most vigorous cultural environments in Europe at the time. There,

he took a course in urbanism at the Politecnico di Milano. He

also studied the work of the Lombardy Rationalists of the 1920s

and 1930s, in particular Terragni and Lingeri, who had first

attracted his attention in London. Out of this research came

the first comprehensive assessment of the Italian Rationalists

to be published in Britain after the war-a strange feat for

a Cypriot-born architect, but only really a surprising one for

Koulermos.

While continuing to shuttle between

his European bases, Koulermos has become a resident of the United

States. Since 1973 he has taught in the Faculty of Architecture

of the University of Southern California at Los Angeles and

has lectured extensively throughout the United States, Britain,

Greece and Italy. His projects have been presented in leading

international reviews, including Casabella, Domus, Arquitectura

and A+U.

An international man, Koulermos has

sought inspiration from the most disparate cultural sources.

Yet his work is unfailingly cohesive, building on his sound

training and firm principles of practice. As a consequence,

he has progressed unchecked though a period that has been very

difficult for international architecture in general-a period of

false turns, of wasted energy. By this, I do not mean to say

that his experiments and research have adhered statically to

their point of departure, unwilling to recognize the changes

wrought by time. Quite the reverse: his architecture reveals

an evident curiosity. He weighs up the battered rhetoric of

ephemeral innovations and passing fashions and extracts from

them the elements worth retaining as a stimulus to thought.

For this reason alone, Koulermos' projects deserve to be subject

of wider attention. Rather like a low-sensitivity film, they

capture the best results of the (often confused) architectural

research conducted since 1960s. As a whole, his work constitutes

a kind of 'critical text' which requires careful reading.

Koulermos' expressive modes have evolved

into a small but steady flow of successful commissions and inventive

design experiments. The latter provide the opportunity to research

issues more thoroughly than would be possible in a real contract.

However, even in the designs produced for pure pleasure, or

for the purposes of testing a new morphological hypothesis,

we do not see the self-indulgent graphics that make much 'paper

architecture' so superficial. Koulermos' designs are always

oriented towards construction, and this gives them not only

the cohesion which we have already noted, but also a healthy

clarity. These features are, I believe, immediately evident

in all of his projects, from the Rationalist early schemes in

London to the most recent experimental designs in Greece , where

the beautiful landscape has formed and natural focus for his

research and built work.

From this point of view, the carrier

of Koulermos represents a modern retelling of an ancient tale.

He has been on a long voyage, facing many trails on the way,

but now he has returned to the land of his birth, a grown man,

mature. Or, to put it in slightly different terms, he has returned

home laden with precious goods collected on his travels throughout

the years.

His work is accumulative. The Scalabrini

Retirement Center in Sun Vally, Los Angeles, which interprets

his interests in Rudolph Schindler, the Tradate School, which

reflects the design culture of nearby Milan , the 'theoretical'

designs for Venice, the projects undertaken with his students

in Los Angeles-all have built upon each other to form a design

language and practice which have yielded their best results

in his recent commissions in Greece.

The Science Complex for the University

of Crete is proof of this. It combines into an articulated narrative

all of the issues on which Kuolermos has been concentrating

so patiently: the memory of the ancient civilisations of Crete,

the lessons of Kahn, the intensive development of elevations,

the constantly repeated vertical slots, the shifts within the

floor plan that are reminiscent of his experiments in Italy.

The result is a firm but open building which is fully aware

of its environmental responsibilities.

While the massing of the Science Complex

is richly narrative, Koulermos' design for the Research Center

and Administration Building of the University of Crete is more

concentrated and explicit-a judicious mix of Mediterranean simplicity

and models reinterpreted from his time in Milan.

These projects demonstrate Koulermos'

ability to filter and select. The task of selection is done

not only with intelligence and cohesion, but with a moderation

that engenders elegance, as we can see in the Nursery School

in Los Angeles and , above all, in the twelve houses based on

an invented programme for twelve different sites in the Hellenic

world. These last works also encapsulate an act of sincerity,

for they clearly record the sources of their inspiration and

the models they are intended to study.

It is evident that Koulermos studies

as he works. For this reason, it is almost impossible to distinguish

between the designs and the finished projects. Seizing every

design opportunity, even to the point of creating a fictitious

client-himself-he skilfully accumulates the material that he

will use in his buildings, selecting everything with thought

and care.

Panos is a prudent and moderate man.

Could there be any higher praise for an architect in our times?

Edited version of article published in the catalogue of the

Panos Koulermos exhibition, Topos, Memory, and Form, in 1990

at the House of Cyprus, Athens.

Interview

With James Steele

In an interview with James Steele in

Los Angeles, Panos Koulermos talked about the development of

his career and the moves which have taken him from London to

Milan to Athens and LA, always in search of light. The discussion

spanned the London architectural scene of the 1950s, the influence

of the Italian Rationalists, and the importance of understanding

what it is that makes a city.

JAMES STEEL: The obvious place to begin is at the

beginning, with your time in London. How would you characterize

that point in your career? What were the influences behind it?

How did it all happen?

PANOS KOULERMOS: It was a significant time in my

life. It might at first appear strange that someone from Eastern

Mediterranean should have gone to England to study, but I think

it's important to seek out a culture that is different from

one's own-a new place to learn from. London in the 1950s was

a good place for organized studies and discourse. I went to

Polytechnic of Central London, which I believe is now called

Westminster University. The period, however, was rather lacking

in architectural vitality, because it was caught between the

post-war Welfare State and a kind of Scandinavian romanticism.

English architectural interests were in general rather soft:

Early Modernism was perceived as too 'Mediterranean', though

there was a partial flirtation with Le Corbusier. Nonetheless,

these were intriguing years. The Poly was basically a good,

solid school with some dedicated teachers. I was also exposed

to many interesting people through my contact with Architectural

Association.

JS: Who were the paradigms for you as a young student?

The Smithsons were active at that point. Lubetkin was in London...

PK: Lubetkin had already dropped out: I believe

he'd become a farmer. He was anti-establishment and disenchanted

with the patronage of the time and with architecture in general.

His primary contribution, as Colin Rowe has said, was 'to establish

Corbu as an English taste'.

JS: James Stirling was a tutor at the Polytechnic

for a short time before his teaching stints in the States. Was

he big influence at the school?

PK: He was a great person to have around, though

of course nobody could have guessed how important he would become.

I still have a clear memory of the time when my tutor, Douglas

Stephen, brought Stirling to look at my project: I knew from

his critique that he was special and different. Stirling was

of the same generation as Stephen, Maxwell and Rowe. They all

studied at Liverpool.

JS: They were all involved with the Polytechnic?

PK: Only Stephen and Stirling were. Bob Maxwell

later taught at the AA. Around this time, Stirling was working

for Lyons Israel and Ellis. He met James Gowan there and they

went on to open an office together. Their first significant

project, the Langham House flats in Richmond, was a definite

breakthrough in English architecture-a major influence, as the

Smithsons' Hunstanton School had been a few years earlier.

JS: This was also the period of the New Towns, like

Stevenage. Where you interested in that?

PK: As students we didn't find them particularly

interesting, or perhaps we didn't understand the issue very

well. To us, they were part of a decentralised plan based on

economic factors. We couldn't get enthusiastic about them because

they didn't have much to do with architecture. The New Towns

were never interesting places for people. They were uninteresting,

solitary camps.

JS: Who or what did capture your interest?

PK: Denys Lasdun and Ernö Goldfinger were very important.

There was also a small group of younger architects with a lot of

talent but no significant work, and exhibitions such as This

is Tomorrow, with contributions from Smithsons, Eduardo

Paolozzi and others, In terms of my life, however, Douglas Stephen

was the most influential person and I will always be indebted

to him. I had the good fortune to work with him after graduating

and he introduced me to a lot of interesting people. I recall

Saturday mornings at the French pub in Soho, which was a famous

gathering place. Alan Colquhoun and John Miller would be there,

as well as Colin Rowe when he was in town...and Neave Brown,

Jim Stirling, Bob Maxwell and Kenneth Frampton, just to mention

a few. These were very spirited, informative social events.

I also think that Reyner Banham's emergence as an architectural

historian and critic was important. He used to write a column

in the New Statesman every Friday.

JS: Can you identify any of the ideas or directions

that came out of the discussions of that period?

PK: Le Corbusier was a tremendous influence, The

good British architects were doing academic Corbu, or rather

an Anglo version of Corbu. I think Jim Stirling's early work,

such as his thesis and Langham House flats, shows the influence

of Corbu. The same could be said of Colquhoun and Maxwell.

JS: Langham House was a private development, wasn't

it? It had a humanistic quality of light and materials, and

conceptually it was very different from other housing projects

of the time. In a way, Stirling was trying to show others how

to do it.

PK: I think you're right. He wanted to show a progressive

way of doing housing-an alternative to the 'romanticised conventionality'

that generally came out of the local authority architecture

departments.

JS: What were the Smithsons doing at this time?

PK: They were working on their entry to the Barbican

competition, which was based on the idea of 'streets in the

air', development theories put forward by Ginsburg in Russia

in the early part of the century. Peter Smithson was also in

charge of the fifth year at the AA while I was teaching there

as a thesis tutor. We learned a lot from him and Alison when

she took part in reviews.

JS: Did Team X ideologies and discussions coincide

with yours?

PK: Some of them did. They certainly coincided with

my education-we used to attend various lectures about their

work. Their theories presented an alternative to doctrinaire

Modernism, to the prevailing systematic and pragmatic approach

to architecture. In my case, however, the major influences were

Le Corbusier and Terragni.

JS: How did you discover Terragni and Italian Rationalism?

PK: Through Douglas Stephen. Very few people knew

of Terragni, because he had died so young. His work had been

published in Alberto Satoris' books, but these were not readily

available.

JS: What was it about Terragni, now that you mention

it, that caught fire with you?

PK: One day Douglas showed me a photograph of the

Casa del Fascio and I had a sense of déjā-vu. It seemed very familiar

to me, but at the same time I knew I had never seen it before.

In many ways, it was the embodiment of what I wanted to do;

an architecture close to my heart-modern, fecund, and Mediterranean.

Aspects of my thesis were influenced by Terragni, blended with

Corbu.

JS: What was the subject of your thesis?

PK: The Greek Embassy in London. Topics have their

moments and in those days embassies were very fashionable. Later,

it was libraries and museums. I chose the embassy because its

programme had a certain potential for formal development. I was interested

in learning how to develop a language of exciting forms. In retrospect,

my concern was not to express function but evolve a concept

that addressed larger concerns, such as the city, order, space

and autonomous form. I suppose this was my 'official' initiation

into Rationalism.

JS: Beyond the visceral sort of interest that you

find with Terragni, is there also perhaps a philosophical connection,

a link through the classical tradition, absolute geometry and

absolute form?

PK: As I've said, I immediately felt a strong affinity

with Terragni.. In my view, he was the one who established the

classical roots of Mediterranean Rationalism, which forms the

basis of my own work as an architect...There are many categories

of Rationalism, not just the formalist, rhetorical kind that

some people think of. Mediterranean Rationalism is a poetic

Rationalism. Rather than making a radical break with the past,

it reinterprets traditional architecture; it makes a connection

with history. To me, this is very important.

JS: What were you doing professionally at this time?

PK: I was Douglas Stephen's first assistant and later

associate partner. I worked with him for five years and the

experience meant a great deal to me. He was a lively, provocative

and challenging person. He was the most significant educator

I've had-and I use the word 'educator' in its true sense; to

mean someone who really brings out who you are. During my time

there I worked primarily on projects for residential and educational

facilities. The major building that I designed with Douglas

was Centre Heights in Swiss Cottage, London, a complex containing

shops, offices and flats. Later on, Kenneth Frampton joined

the office and worked on a block of flats in Bayswater. Douglas

let each of us take on one or two projects and follow them all

the way through from design to construction.

JS: You mentioned that you were also teaching at

the same time.

PK: I was teaching at the Architectural Association.

In a way, it was one of the most exciting times of my life. Though

the AA was not the AA of the post-war years, it was still a very

lively place. Cedric Price was there, so were members of Archigram

Group-Ron Herron and Warren Chalk.

JS: So why did you decide to go to Milan when you

were involved in so many challenging things in London?

PK: I felt I could not possibly live all my life

in England. I missed the light and warm weather. I used to dream

of the blue Mediterranean sky and I realized that light was

an essential part of the architecture that I wanted to do. The

architecture of the 1930s was primarily Mediterranean in conception;

it needed strong light. So, too, did the work of Corbu, with

its combination of Classicism and Mediterranean vernacular.

You need to have the right context and climate. This is made

clear by Aldo van Eyck's orphanage school in Amsterdam. It's

a outstanding building, but if you see it on a cloudy, dark

day, it appears dull, alienated. When the sun is shining, however,

the organisation and forms come alive; it makes sense.

Milan is not exactly a sunny hotspot,

but it is better than London. My concern was to learn, and Milan

was an important cultural centere. Italy was also a country

where I wanted to live for a while; a kind of stepping stone

towards the Hellenic Mediterranean. At the suggestion of Kenneth

Frampton, who had become the new technical editor of Architectural

Design, I started to research a special issue of AD

on Terragni and Lingeri. This Magazine (of March 1963)was the

first post-war English publication on their work.

JS: Did you start it while you were still in England?

PK: No, it was something I did in Milan. It was

really Kenneth's decision. He knew my affection and admiration

for those people and he said 'Let's publish something'. I completed

the research in a year in spite of the difficulties in getting

the material. People were very critical of that period, associating

it with Fascism. As a outsider, I had also to learn how to operate

in Italy, how you get around people, I felt that it was very

important to get the publication done while Lingeri was still

alive, so my wife and I went to visit him frequently. Lingeri was

charming, warm man and he was able to tell me a lot about Terragni

and Sant'Elia, with whom he had worked for a while. This experience

really marked the beginning of my interest in historical and

theoretical research.

JS: I am interested in learning more about your

professional transition from England to Italy. How did you come

to Milan?

PK: Milan is not like Rome or Florence or Siena.

Piera, my wife, warned me that Milan was not going to be easy.

It is a tough, fast-moving business centre. There is no time

for dolce far niente or idling in the piazza. In the

end, it was an arduous but worthwhile move...and the beginning

of a long, perhaps romanticised affair with Italy which continues

still, both personally and academically, 30 years on.

JS: What other elements of study did you get involved

in during that period, besides the connections you made with the

Terragni publication?

PK: I researched educational facilities and got

involved in substantial studies of housing projects for various

public and private organisations. I also became absorbed with

urban planning and attended the postgraduate course in urbanism

at the Politecnico di Milano. I think it is vital for architects

to study the larger context in order to understand the city

and the socio-political complexity of their work. Buildings

cannot be designed in abstraction and in isolation, for they

are an element of our culture.

JS: Would it be fair to say that you are looking

at urban design and planning as an area of study? Modernism

hasn't typically focused on urban planning, with the exception

of Le Corbusier and perhaps Kahn, but it tends to be an area

of interest in Rationalism. Am I right?

PK: In England, I found that planning was done by

planners; architects never got involved. As a consequence, the

urban masterplans were not physical plans; they did not deal

with urban form. In Italy, there were no planning schools as

such. Planning was a component of an architect's training, a

specialised course you could take. People generally assumed

that an architect would also be a planner- a misconception,

as being good at one doesn't make you good at the other. Often

architects have no understanding of what makes a city. In the

post-war era there was a tendency to consider the city as 'one

building', to be organised in a regimented way in the name of

simplicity and rationality. The result was a standardization

of the built environment. The attractive qualities of the older

cities were lost. People found the new buildings oppressive

and impossible to relate to. That was the beginning of a problematic

period in planning. The buildings themselves were sometimes

interesting, but the open spaces, the 'voids', were not. In

many cases, you had either bad planning and interesting buildings,

or the reverse: good planning and bad buildings. In England,

unfortunately, many of the New Towns were bad in both respects-

uninteresting as planning paradigms, and unrewarding for the

people who lived in them.

For a number of years there was

a kind of stagnation. Modernism was in crisis and architects

did not know which way to turn. The Italians provided a way

of studying urban planning and architecture. Aldo Rossi's The

Architecture of the City deals extensively with the subject,

as does Carlo Aymonino's The Importance of the City,

which was written around 1975. They were concerned not with

methodology or social policy, but building typologies and the

city. Of course, this is not the only approach. In the United

States planners are interested only in policies; they do not

want to become involved in design. Yet policies are meaningless

unless they are manifested in physical form.

JS: The urban spaces of Rome have the Nolli quality,

in that interiors and exteriors are unified. Is Milan the same?

PK: No, because Milan is primarily an 18th/19th-century

city, with a sprinkling of medieval sections, early paleo-Christian

churches and Roman ruins. Rome is more historical. Its City

fabric gas been built up over the different epochs from ancient

times to the present. The urban form in its historic centre

is unique. It has wonderful public spaces such as the Campidoglio

and the Spanish steps. Experientially, Rome is inspiring and

alive-and would be even more so without all those cars, of course.

It's worth studying the interdependence between urbanism and

architecture.

JS: Did Milan, in a same sense, become an urban

textbook for you when you were there?

PK: Milan is not yet a typical city. Its 18th-and

19th-century buildings are engaging because they are a fusion

of Central European and Italian ideas. The influence of Vienna

and France is clear. De Finetti's Meridiana apartments, for

example, are inspired by Adolf Loos. They show the gradual evolution

of Modernism- the transitional phase before it became a doctrine

with strict rules and iconography-and they have a discreet connection

to the past. Milan is a dynamic city where things happen. It

is not somewhere you go to find 'romantic' cityscapes, although

the centre is a captivating and quite remarkable place. The

problem with Milan and other European cities is urban sprawl.

We have been unable to create good urbanism so far this century.

JS: How would you characterise the influence of

the city on your career, coming from London and then working in Milan

from a period of time? How would you say it related to what

you were interested in?

PK: I think it has tied in very well. My education

in London was about Rationalism, so moving to Milan was like

going to the Rationalists' home turf. Even though I was extremely

fond of London. I've never regretted leaving because I think

it was vital for me to get out...just as later on it was vital

for me to get out of Milan and go to Athens. I've always felt

the desire to learn and to be challenged. I'm not a person who

is easily contented. For me , work is not about running around

in order to make money; It's about learning in order to avoid

stagnation and, above all, provinciality. It is astounding how

quickly one can become provincial. I've also moved in search

of light and warmth...

JS: So, after leaving Milan, you went to Athens?

PK: All along I really wanted to go back to the

Mediterranean - to Greece and Athens, which was the major city of

the Hellenic world and, for me, the right place to be. I opened

an office with Spiros Amourgis, whom I'd met in London, and

Nicos Kalogeras. It was a very exciting step and an incredibly

important period in my life. We were committed and energetic.

I also found that at last I could begin to apply some of the

knowledge that I had acquired in the right context-the Mediterranean!

JS: How did you break down the various roles within

the partnership? Were you the design influence?

PK: All three of us were interested and involved

in good design. We were oriented much towards design than business,

but we all found our own roles. In general, one partner would

answer to the client and administer the project in collaboration

with the others.

JS: What was the general scope of the projects you

worked on?

PK: We had very diverse work: housing, educational

facilities, industrial buildings, office buildings, libraries,

airports and planning schemes. We also took part in competitions

to test out some of our theoretical ideas, and were quite successful

in a number of them.

JS: This was a period of time in Athens, if I am

correct, when there was a housing shortage.

PK: A shortage of good public housing, yes. The military Junta was in power, and it took a lot of the joy out of life and work. Even so, I have no hesitation in saying that those years were really the happiest of my professional life so far. They were formative years. We were also very idealistic and wanted to help establish a better attitude towards architecture in Greece. We founded an institute, which we called the Workshop of Environmental Design, and organised international summer programmes for six years. We had no grants - nobody gave us any money - but we had energy and passion. In spite of the military Junta, in spite of the political situation, it was a full, intense and meaningful time.

JS: Did you maintain your connection with Italy

and Europe?

PK: Of course, I was going back and forth all the

time to work on some educational facilities in Milan. During

this period my whole image of the city changed- the place appeared

more friendly. The Milanese at first seem cold and distant,

but they are really discreet; friendship just takes time to

develop. Now I am happy to say that I have remarkable friends

there. I've taught at the Politecnico di Milano and I also have

an ongoing academic relationship with the School of Architecture

in Venice ( IUAV), which started with an invitation from Carlo

Aymonino, who was then its director, and Gianugo Polesello.

In 1966, I began my 'official' academic career, teaching as

visiting professor at various universities in the United States.

JS: That period coincides historically with an enormous

intellectual upheaval in Italy, the Tendenza. What was

your connection with that?

PK: I don't really think that you could describe

what went on as an 'upheaval'. The Tendenza is a strange

phenomenon, because in the beginning it was recognised only

outside Italy. Very few Italians knew about it.

JS: Was that the name given to it by outsiders?

PK: The Tendenza was an approach towards

architecture advocated by Giorgio Grassi and Aldo Rossi. It

was a trend, a very selective kind of view. My main connection

with it was through a traveling exhibition called Rats, which

showed the work of Ungers, Rossi, Aymonino and Grassi, among

others. When the exhibition came to Los Angeles in the 1970s.

we invited all the participants to give a lecture. The event

generated a lot of discussion and interest during a period that

was deprived, to say the least.

JS: Did the Tendenza start in Venice, where

Rossi was teaching?

PK: No, it was a Milanese movement. As I have previously

mentioned, Rossi's Architecture of the City was very

important book because it provided a theoretical treatise about

urban typography. Post-Modernism was emerging at that time too.

Architects incorporated historical motifs into their designs,

responding in a rather scenographic , superficial way to the

past and to a place. The problem was that they often did one

building at a time without understanding its relationship to

the rest of the city and to the other buildings. I do not subscribe

to the idea that if you know how to do a house, you know how

to do a city. The two things are not the same.

I think the Italians have contributed

significantly to a more considered attitude towards the city.

In Italy, Post-Modernism never really established itself as

a major movement in the same way that it did in the United states

and, to a lesser degree, England and France. Italy has enough

real history not to feel the need to create a false one. Italian

students were very critical of that whole Post-Modern period,

as they are now of Deconstruction. They still operate freely

within the Modernist and Rationalist ethic.

JS: This brings us to your academic involvement,

a significant part of your career. You have taught since 1973

at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and

it must cause some philosophical dichotomy when you see how

the students operate here. Unlike Italy, they are looking for

trends.

PK: Fortunately, not all of my students in LA have

been trendy- a lot of them have done quite serious work. Because

of the non-historical milieu, they tend to be open-minded and

to have a stylistic propensity. But this freedom also brings

about a less critical way of thinking. The city defines no rigorous

rules of operation; there are no infill projects, no areas of

urban compactness. You can do whatever you want, up to a point

of course. Many architects practicing in LA are trying to do

their own thing, and their self-indulgence and egocentricity

have created an array of idiosyncratic buildings, some good,

some bad, which together don't make up a city.

JS: Since you have a international outlook you can

look quite objectively at this city. What do you think this

lack of regard for urbanity means? Are architects here isolated?

Will LA ever be more than all these centres in search of a centre?

PK: First, I think it's very wrong to call Los Angeles

a 'city of many centres' - I only whish it were. Rather than

having urban centres like Paris, London or Rome, it has concentrations

of commercial buildings, of stores or gallerias. These are not

'centres' in the true sense of the word. This is not true urbanity;

it does not help people to create a compatible society. Los

Angeles has to offer its inhabitants other options than auto-mobility.

Life here is highly programmed; you cannot do things casually.

Environments create attitudes and LA has to start thinking about

its collective well being. We have to address issues which I

think are pertinent to this city and find a way to create places

where people can live together. Maybe then in 150 years we will

have a good city.

Interview

With Tefchos Review

In this interview, the Greek review

Tefchos talks to Panos Koulermos about the design of

his building complexes in Crete for the Research Centre of Crete,

and the university of Greece, one completed, the other under

construction. Naturaly enough, the discussion touched on a large

number of other matters, such as the firm principles which underlie

his work and the relationship between context and building type

in architecture. Included among Tefchos' participants in the

discussion, which took place in Athens, were the following architects:

C Papoulias, Y Simeoforidis and Y Tzirzilakis.

TEFCHOS: In your lecture at the House of Cyprus

you said that in the last few years, and particularly in your

designs for Crete and Spain, you have been concerned with rigorous

forms, powerful forms. How, exactly, do you perceive this?

PANOS KOULERMOS: The basic architectural vocabulary

of my work is that of articulated pure forms. I think that large

public buildings (the res publica, as Toy Garnier used

to say) ought to be powerfully geometric, in order to assert

their presence and urbanise the surrounding area. They ought

to be points of reference in the disorderly environment that

one usually finds on the edges of Greek cities. The site of

the Research Centre of Crete lies next to the existing University

of Crete building, just outside Heraklion on the road to Knossos,

in amongst endless houses and blocks of flats without any form

or order. When I saw it, the first thing that occurred to me

was to create something highly geometrical and powerful. In

fact, all the first ideas that I had for this project were geometrical

in building terms, though some elements, like the Technology

and Research Foundation, were perhaps a little more freely organised.

I never produce buildings which are not rectilinear, that is,

which are not geometrical.

T: The buildings are set in natural environment.

But the chaos of the city could be said, to some extent, to

follow us into nature. Is that why your buildings have a concept

of order within them?

PK: Perhaps, because a juxtaposition takes place.

The buildings as an artefact is juxtaposed against the natural

landscape without any attempt to soften that relationship. The

antithesis between nature and building is powerful one, which

is in fact a very Greek characteristic. Integrating a building

into the landscape does not mean making it disappear. I think

that one of the most serious problems in Greece is that everyone

builds in a scattered manner, destroying nature, when it would

be preferable to group the buildings together. How you see a

building, whether it's clear, the strength of its presence in

the landscape-those are very important things.

T: You often use the word 'see'. Is it ultimately

a matter of vision? What does 'seeing' really mean?

PK: To see, to read, to interpret. From a distance,

you see the general form and articulation of a building: you

cannot distinguish any details. As you approach, however, the

tectonic structure unfolds and you begin to see the various

elements. Notre Dame, for example, has a marvelous volumetric

form and articulation, with its flying buttresses, when seen

from a distance. As we approach, the image of the building is

enriched with the details, the materials and the colored glass,

the statues, the interior, and so on. The first reading, from

the distance, is of great importance in every building I design.

The rapport between the building and the land is the first thing

that interests me. This is followed by the spatial organisation,

the articulation of the elevations, the interior, and a variety

of other experiences which transform the masses into habitable

buildings. Buildings evolve in the same way as a city. La Tourette

is a major reference in my work, particularly in relation to

the first and successive readings of the building. Seen from

a distance, it appears to be a vast stereomorphic mass dominating

the landscape. Yet when you approach the building and enter

it, the scale changes at once and a 'modest', human environment

is created.

T: I t could be said, none the less, that there

is a difference between La Tourette and the Crete buildings

precisely at the point where one enters them - a difference in

the organisation of the interior space.

PK: The buildings in Crete are based on the idea

of a city, and more specifically on the idea of the city centre.

There is also a dynamic interdependence between the macro and

the micro scale. I think this is the role played by

architectural form: it meditates the transition from one scale

to another, from the urban scale to that of the building. When

we study a building which is not part of an urban context, we

have to find, and generate ourselves, the points of reference

and relationship; that is what I mean by space urbanisation.

T: The ability to read a building from a distance

reminds us, apart from La Tourette, of the monasteries of Mount

Athos or Sinai. In these complexes an inner lack of order lies

behind the surrounding wall. One can see this relationship in

the Crete buildings, especially in the Science Complex, which

is organised like a little town. There is a geometric form,

with the mountain in the background, running down to the sea.

At the same time, this form leads us to the concept of the 'monument'.

I know you have your reservations about the word, but it exists

all the same. What sense do you ultimately give to the monument?

PK: Jefferson said that architecture is a useful

art in the full sense of the word, and I don't think he meant

just 'functional'. Monuments, to me, are not a 'useful art'.

The use of the syntax of architecture and teconic forms exclusively

for symbolic purposes gave rise to both the Vittore Emanuele

Monument and Palazzo del Civilta' del Lavoro in the EUR district

of Rome. Fortunately, this is a tradition which has not yet

arrived in Greece. I would also say that for me 'monument' means

something closed and frozen, in which human life plays a secondary

role. But the word has been misused for many years, in good

faith, perhaps. I think it is better to refer to the question

of organisation of scale and form instead. In the Crete buildings,

the primary significance lies in the natural and the human environment.

I would prefer them to be seen as 'temples' to man and life.

T: In a recent text Ignasi de Sola-Morales proposes

a different concept of monumentality as an echo of the monuments

of the Classical Age, as what art and architecture can produce

when they manifest themselves not as aggressive and domineering

but as 'tangential' and 'weak'. However, the Crete buildings

display a marked desire to dominate the landscape.

PK: I had a reason for designing those buildings

the way I did: I think there are not enough examples in Greece

of buildings which try to generate a powerful relationship with

their context. The Crete buildings correspond to small hill

towns; they are 'landmarks' in space. Each unit in these complexes

has its own integrity and, at the same time, is connected to

the rest. We designed the piazza of the Science Complex as a

large public space. It is not a piazza for biologists and chemists

alone, but a piazza for everyone - the urban piazza of the university

as a whole.

T: Let's go back to the question of vision, to

what we were saying about 'seeing'. The sizeable presence of

your buildings brings about a major transformation of the existing

landscape. What is it that you want to be 'revealed'?

PK: The visual connection between the landscape

and the city is of great importance, as is the relationship

between the buildings themselves. It is very important that

we should have an overall view of a building or of a city before

entering it. This is an experience based on movement, memory

and the reading of the buildings and urban areas which we see

in succession; the urban stimuli. This is the principle which

we have followed in our designs for Crete. The large piazza

of the Science Complex is approximately 110 metres long and

is at right angles to Mount Psiloritis, thus establishing a

visual bond between the building and the landscape. The same

idea is repeated in the galleria of the Foundation of Research

and Technology, which is about 65 metres long. This type of

organisation and form was evolved in such a way as to celebrate

the presence of the landscape which surrounds them. If that

kind of landscape and topos and an understanding of its

history had not existed, we would not have proposed these ideas.

Of course, I owe the conceptual inspiration to Kahn's Salk Institute

and to the court of Phaestos. That is one of the constant elements

in my work: I always try to create buildings which have roots

both in their land and beyond it. This does not mean 'regionalism',

since the magnitude of the concept of the topos varies

from person to person. In my case, I mean Crete and Greece in

general, with references to the Mediterranean tradition of Rationalism

and 'evolutionary Modernism'.

T: This is the point at which Frampton's critique

comes in. In the text in which he presented these designs in

Casabella, he referred to the topological organisation

of the buildings and their relationships with the site.

PK: Frampton referred to the type and size of the

Science Complex and to its relationship with the terrain. He

believes that the type dominates the site. Perhaps he would

have preferred smaller units, more freely organised in space.

In its section, the complex exploits the slope of the ground.

Of course, the size of the laboratory units meant that large

bases and podiums were necessary. In addition, as I have mentioned

before, I believe that strong unified forms are more suitable

for this landscape. Frampton cites the Knossos palace as an

example of a building that, with its inflections and different

levels, sits well on its site. I think the opposite is true.

Knossos is an extremely geometrical and rigid megastructure

which has many levels connected to each other by larger or smaller

staircases. Frampton may not have been thinking of the south

side of Knossos, with its large bases, high retaining walls

and stepped portico. And he may also have forgotten the western

side, with the 'customs house" building, whose base is equal

to its height. This is the condition of contrast we touched

on earlier. In any case, we are not talking about small residential

units but about large public buildings. In my opinion, what

is important in these cases is the architectural and planning

entity and not the type, which can be scrutinised as an isolated

phenomenon. These designs do not deal with one single building

but with a number of them. They are predicated on the models

in which a large form dominates the landscape, as is the case

with the centre of ancient Miletus or the Italian cities of

Urbino and Assisi, rather than the paradigm of island towns,

in which the final form is the accretion of many smaller forms.

T: However, perhaps we could claim that after the

triumph of typology over topos, there have recently been

efforts to redefine that relationship. What does typology in

architectural practice mean? What role does it play in design?

PK: There is a typology in terms of the plan and

in terms of the form or formal association. I believe that both

of these stem from the fundamental organising idea and from

the dynamics of the topos and the land. I do not mean

that in the way a surveyor would see it, but in the sense of

the broader context; that is, context is site. I think that

this view is the opposite of the beliefs of some of the Tendenza

architects, who often make an a priori choice which

satisfies, first and foremost, their philosophical position

or the local architectural culture, ignoring the other design

criteria or, if not, reducing their importance. In the Science

Complex the choice of the "portico" for the ground floor of

the teaching building was made in order to establish a dynamic

relationship with the piazza: so what we really have is an urban

idea giving birth to a type. The idea of the "grand gate" created

by the double-ended opening in the centre of the building dominates

the organisation and expression of the various spaces. The principal

thought, the formal association, was the city wall and gate.

Here, there is a reference to the type/form. The typological

organisation of the ground floor portico is volumetrically differentiated

and leads to forms related to the more general concept of the

complex.

Construction also follows this central

idea. Construction means building space, and it clearly has

a language of its own. What I mean is that one doesn't design

by drawing floor plans without having any image and form in

mind for the building, or in other words, elevations. Kahn said

that architects ought to be composers of elements, rather than

designers. Construction has played a very important part in

my work and has often assumed a predominant role in the form

of the building. I think the spirit of the tradition of Rationalism

and that of Le Corbusier and Kahn have revived a richer repertoire

of architectural thought and expression, one which overcomes

the worn-out and sterile Functionalist mentality.

T: Your reference to what you call the tradition

of "evolutionary Modernism" and its connection with Italian

Rationalism brings us back to a debate which has been almost

forgotten. Tell us something about the point at which your personal

work intersects with that tradition.

PK: The work of Le Corbusier and Giuseppe Terragni

had a great effect on me when I was a student in London. The

influence of Le Corbusier is clear in my thesis for the Greek

Embassy in London in 1957, where I proposed to transform the

'Classic Modern' linear type of building into a typologically

complex combinational building by placing a cylinder between

two rectilinear towers sharing the same base and cornice. This

was, for me, an exercise in a three-dimensional solution which

made use of pure forms on a large scale. Some people in the

school saw the proposal as iconoclastic and ostentatious (this

was, after all, the Dark Ages of the post-war period), but it

led me to understand the potential range of 'powerful forms'

in space and the significance of light in architecture. I realised

that some forms provide more of an urban nature than others,

and are more evocative, too.

This interest of mine was continued

in Milan, and then in Athens in 1965, where my good friends

and associates Spiros Amourgis and Nicos Kalogeras and I designed

a series of buildings which fluctuated between two basic conceptual

categories. In the first instance, the form of the building

had a dominant position as a way of urbanising space (eg, our

design for an office building in Omonia Square). The principal

feature of the second category was the infrastructural grid:

urbanism was an inherent element in the architectural concept,

which was then expressed in rather neutral and undifferentiated

forms (eg, the design for the PIKPA hospital for handicapped

children, or Alexandroupoli airport). These designs were influenced

by the social debates of the 1960s and were also inspired, to

a certain extent, by Aldo van Eyck and Shadrach Woods. Woods'

proposal for the Berlin Free University, in particular, demonstrated

a 'new-old' way of organising a large complex and, regardless

of the constructional outcome, I consider that organisation

to have been one of the most important theoretical concepts

of the century, together with Le Corbusier's proposal for the

hospital in Venice, which is perhaps his only building complex

based on the 'idea of the city' as a unified, low and continuous

city fabric and form. During the 1970s, I was more closely involved

with designs of the second category. The complex for the Scalabrini

Retirement Centre (1973-77) in Los Angeles was in a way the

concluding climax of this phase. However, I have carried the

lessons learned in the 1970s over into more recent work. I have

never ignored previous experience and research; I simply continue

it and transform it in a new situation. What I realised was

that most of the infrastructural projects were right from the

social and functional point of view: they could be built in

stages and were easy to expand. Unfortunately, however, they

were not points of reference vis-à-vis the context and they

were morphologically too neutral.

T: Neutral forms and democracy were typical of

that period. The tendency to return to more geometrical forms

came later, and was connected with the reacquisition of urbanity

and the Tendenza.

PK: That was not true in all cases. I think, for

example, that Aldo van Eyck's orphanage school in Amsterdam

is one of the most significant buildings of modern architecture:

its only problem is that it needs to be in a place with sunlight.

My design projects for the Masieri Foundation Hostel and the

Community Recreation Centre at San Francesco della Vigna, both

in Venice, re-established my interest in the city, and the relationship

between the building and its context, in the late 1970s. This

'return' to pure forms was perhaps a counter-proposal to the

pseudo-historical interests of Post-Modernism. I believe that

people were in too much of a hurry to put Modernism on ice,

as if nothing had happened since the 1930s. For me, every period

has its modernity.

Frampton says it was the work of Kahn

which led the Tendenza to return to its Rationalist roots.

Although I share some influences with the Tendenza architects,

there are lots of ways in which we are different. My Rationalist

roots lie closer to Terragni and Libera. I am interested in

the past and the present, not the pre-industrial period and

its typologies. The Tendenza seems to have become an

enormous basket into which historians stuff everyone. What is

important, to me, is that during those decades conscious attempts

were made to stir up and clarify theoretical and compositional

principles for large-scale buildings and their relationship

to the city. For that change of direction, I may owe a lot to

Louis Kahn. As Frampton quite correctly points out, the Crete

buildings are a 'unique synthesis of mass-form and Rationalist

space'.

T: What led you to become involved with Italian

Rationalism and with Terragni?

PK: When I was a fourth year student, my tutor

Douglas Stephen showed me a photograph of the Casa del Fascio.

I felt a powerful attraction to the beauty of that building.

I was very struck by its form and impressed by its modern, Mediterranean

spirit. It touched my heart, as Corbu would have said. That

was the birth of my interest in this very important period of

architectural history. The elevations of the Casa del Fascio

were designed with outstanding skill. We can see a thematic

idea being developed as a representational element, in three

differing but harmonious ways: the frame, the wall, and the

frame and wall together. We can also see the spatial relationship

between the frame and the wall located behind, in front of and

between the columns. I interpret Terragni's work intellectually.

I think his references to history are very important, and so

is the manner in which he connects his buildings to the city

and the topos. Terragni's interest in 'tradition' was

typical of the Gruppo 7 architects. Their philosophical

position, that 'tradition transforms itself and takes on a new

aspect beneath which only a few can recognise it', was diametrically

opposed to the views of the Futurists, who wanted to flatten

Venice and destroy all the historic city centres. The visual

relationship or dialogue between the Casa del Fascio and its

context is made clear by the formal resolution of the pergola

on the top level of the building which 'frames' the view of

Como Cathedral. Furthermore, the siting of the building and

its main elevation determine the edge where the public part

of the piazza ends. Terragni's interest in the city is quite

manifest in this case.

T: That period, the 'spring' of Italian Rationalism,

was interrupted and has never really been continued, if we overlook

some examples from the Anglo-Saxon side, and from the New York

Five in particular. Is it possible to tap again the vein of

what, in the end, is a singular form of Modernism? Is there

something unstated, something binding, which has made architects

afraid to carry on with it?

PK: It has a difficult social and political background.

Terragni went up like a rocket and his untimely death put an

end to the evolution of that Rationalism. The whole period faded

out under a veil of shame and guilt. The appearance of Rationalism

coincided with the rise of Fascism; it became equated in the

minds of the people with Fascist authority, so naturally after

the war there was a great deal of antipathy towards it. There

were no mass media to inform the people that others in Europe

were building like that, too.

Of course, the objective historical

assessments that we can make today were not possible at the

time. We also don't know for sure what role MIAR (the Italian

Rationalist Architects Movement) actually played in Fascism.

Nor should we forget that this was a time when Italians were

looking for realism and certainties. Architects such as Frank

Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto were fashionable then, following

Bruno Zevi's promotion of 'organic architecture'. This was the

period of the early works of Carlo Scarpa, Ignazio Gardella

and Franco Albini, who were seeking 'softer' forms for their

buildings. The Torre Velasca block in Milan by BBPR signalled

the end, in 1958, of the period of the International Style and

CIAM.

T: Even now the architecture of Terragni has not

really been restored to its rightful position in Italy. Perhaps

we can make another hypothesis: that this is because it draws

on the purism of Le Corbusier and the traditions of the Mediterranean.

It contains an element that is missing in the architecture of

Italian neo-Rationalists - the passage from the organisation

of the floor plan to the expression of the building.

PK: I agree. The lyrical and plastic expression

of Terragni's work is not to be found in the repertoire of the

Tendenza. In the Casa del Fascio the relationship between

plan and elevation turns into a wonderful game, a narrative,

as Giovanni Michelucci would say. You begin with a frame in

space, which you then convert or transform. The frame is what

holds all the elevations together. Its existence is perceptible

everywhere, regardless of whether or not it is always visible.

In this project we can see the fundamental difference between

Rationalism and German Functionalism. Italian Rationalism is

the expression of a general idea and not of one specific function.

This means that buildings can lend themselves to a multiplicity

of uses. Essentially, it deals with a broader programme. Without

being told, you would not know that the Casa del Fascio was

the club of the Fascist Party. The building says nothing about

being a club. It symbolises and expresses a sense of authority

and publicness; it might equally pass for Como Town Hall, or

a number of other things.

For me, the work of Terragni is intellectual

and not formalistic. When I look at his architecture I feel

that there is still hope in the world. None the less, I would

like to pause for a moment over the difference between the Casa

del Fascio and the Casa Giuliani-Frigerio. The latter has an

awkward floor plan with very little articulation. There are

three apartments, which lie parallel to each other, to the staircase

and the main road. This is where we find the famous resolution

of the section: you go down from the landing to enter the third

apartment through an access balcony that lies behind one of

the other apartments. The frontal expression of the building

on the three sides bears no relation to the basic organisational

idea of the spaces. What interested Terragni in this building,

I think, were the theoretical repertoires of expression and

the syntax of the organisation of the elevations, regardless

of the arrangement of the internal space. I find that project

simultaneously educational and unsettling. It was the last building

Terragni worked on, and perhaps his most narrative and challenging.

T: We believe that we ought to turn our attention

to uniting the Functionalist and Rationalist elements, which

today present themselves as separate -and perhaps even contradictory

- through this specific historical progress of architecture.

Let us think for a moment about the distinction between the

Italian and German 'traditions of the new'. In your lecture

at the House of Cyprus, you said that the idea of the city held

by the German Functionalists was a little strict, a little rigid.

PK: The 'typologies' of the hard-line Modernists

cannot create a city.

T: Wasn't the proposal by Terragni and Sartoris

for the Rebbio district part of the same rationale?

PK: I must admit that I'm not certain about that

proposal. Terragni's intervention in the city of Como (the Cortesella

district, 1940) is a problem, too. I think it's a harsh intervention,

in terms of urban scale.

T: Yet designing a whole city, or even a part

of it, is not the same as designing an individual building.

Of necessity, we have to relate the problem of economical and

social housing with the problem of changing scale. The programmes

of the Social Democratic town councils in Germany, for example,

have not confined themselves solely to the question of Functionalism.

PK: I think there are other solutions to the problems

of social housing, and we don't have to end up with slabs or

blocks. We tried to achieve a more human scale in a housing

project in Milan, with staircases, patios and relatively low

buildings. With such a rationale, you can quite easily begin

to make typological combinations and, in the end, create a city:

something that is very difficult to do if you base yourself

on the logic of the one-piece, one-type block.

T: Here you seem to be criticising post-war architecture

more than the Modern Movement. However, the examples of the

Siedlungen in Frankfurt are of extreme importance and

we believe that in the area of the typology of social housing,

and particularly of its equipment, things have in effect not

progressed since the time of Wagner, May, Taut, Hilberseimer

and Oud.

PK: I agree. I do not want to underestimate such

work, but those were small and isolated phenomena and, regardless

of whether or not they were successful as ideas, they did not

become models for post-war planning. Here I am referring to

the type of town planning which is not just a repetition of

a 'typical unit' in space. The city is not just a block. We

only have to look at the layout of Rome, of Paris, of Vienna,

to realise how rich the urban organisation of their buildings

is. Too often we see the destruction of historic centres as

a continuing urban fabric is replaced with independent and unrelated

buildings. I still believe that slabs and other independent

buildings which cannot be combined cannot make a city, and neither

can the so-called 'Deconstructivist' buildings.

This edited version is reprinted here by kind permission

from the Editorial Board of Tefchos International Review

of Architecture, Art and Design, Athens.

Continuity and Transformation in the Work of Panos Koulermos

Yorgos Simeofordis

The plan expresses the limits of

Form. Form, then, as a harmony of systems, is the generator

of the chosen design. The plan is the revelation of the Form......Architecture

deals with spaces, the thoughtful and meaningful making of spaces.

The architectural space is one where the structure is apparent

in space itself....

The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis Kahn, 1962

During the 1960's the architects of the 'intermediate generation'

born during the 1930's faced the now famous dilemma: continuity

or crisis in the tradition of the Modern Movement? At the scale

of the city and the urban project, European architectural culture

began a critical dialogue with its past. Divergent paths opened

up, particularly in Italy, prompting Reyner Banham to accuse

Italian architects of 'retreating' from the principles of Modern

Movement.

In Greece similar mood prevailed. Indeed,

we can identify a kind of architectural spring, beginning at

the end of 1950's, that coincided with the neo-Brutalist period

of architecture in the country. Yet with the dictatorship of

1967, these efforts faded away. The collective dream of an entire

world sank into a morass of silence. Only a few architects kept

up their theoretical and design inquiries within the 'modern

project', striving to escape the deeply-rooted mythologies of

the Greek tradition.

Among these efforts, particular attention

should be devoted to the work of Panos Koulermos, who came to

Athens in 1965 after describing a trajectory through Europe,

from north to south. He brought with him a Rationalist background

from London (from studies at the Polytechnic of Central London,

teaching at the Architectural Association, and an associate

partnership in Douglas Stephen's office) and valuable experience

from the natural cradle of Italian Rationalism in Lombardy.

This first professional period of work in Athens, which lasted

from 1965 to 1973, marked the beginning of a partnership between

Koulermos and the architects Nicos Kalogeras and Spiros Amourgis.

Together , they shaped a challenging practice which placed particular

emphasis on interdisciplinary research and on education and

culture in general. On the architectural level, the main focus

was on the organization of the floor plan and section in terms

of the tectonic logic of the building.

Koulermos has continued to develop his

work against this background of 'change in continuity'. Although

based in LA since 1973, he continues to move diagonally across

cultures, between the vast city of Reyner Banham's 'Four Ecologies'

and Athens, often stopping in Milan and Venice on the way. He

combines teaching with practice. His work revolves around competitions,

commissions and research designs. All of these have a cohesive

spatial organization which comes out of an unrelenting theoretical

process nurtured by his experience in the classroom and the

workshop.

Koulermos' designs for Los Angeles ,

Venice, Milan and Greece, in particular Crete, express a clear,

balanced relationship between the rational and the symbolic

essence of architecture. The rational is embodied in his public

buildings: the Santa Monica Art Center, the Hollywood City Hall

and Los Angeles Nursery School all convey a deliberately 'timeless

horizon', attained through an abstract elaboration in the design

process of the rational elements of the architectural tradition.

The symbolic element is most frequently present in his designs

for private residences or other small projects, such as the Greek

Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, which have a mytho-poetic

narrative. The concepts of topos, memory and form have been

at the heart of Koulermos' work in recent years, but they have

acquired a personal tone free of the nostalgic emotional charge

that is all too common in contemporary architecture. These concepts

are not articulated in ways defined by Frampton's 'Critical

Regionalism', by the geographically unique notion of 'place',

or by building techniques. Koulermos insists on evoking the

memory of formal associations on the basis of spatial experience,

rather than style.

It was Alberto Sartoris who acknowledged

the central features of modern Greek architecture: simplicity,